TATURA

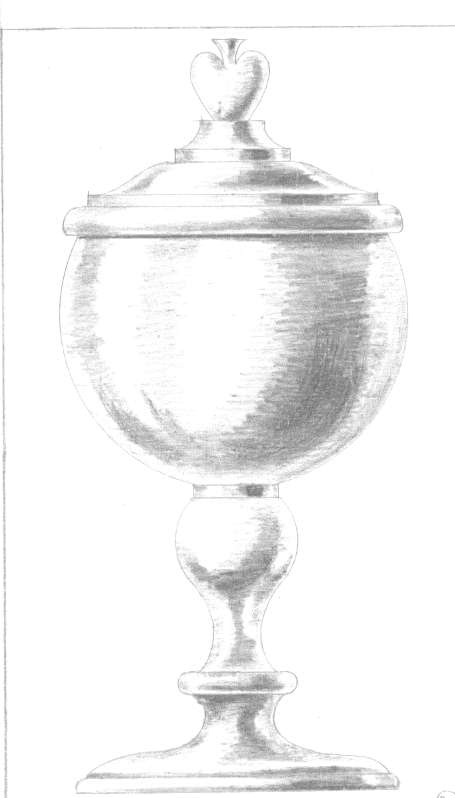

In Tatura, life went on much the same as it did in Hay, but being a fruit picking area, we had working parties going out fruit picking. One guard to every fifty or so internees that went out on working parties. And life was considerably easier. We established a workshop, and I finished up, in the workshop, building my own machinery a bits and pieces from motorcar springs that the working parties brought back. I actually built myself a wood turning lath. It was made entirely from wood – the flywheel was made from wood, the bearings were made from wood, the bed was two six by threes. Most of the wood was offcuts from when they built the camp. The wood of some of the Mulga roots was better than metal; you could hardly drill a hole in it. The drive belt was made of three or four army belts clipped together with wire. It was driven by a pedal.

There was a hut we turned into a workshop. We started off with an axe and a saw, and everything else was home made. We made hand saws out of spring steel, from clock springs. We made a furnace out of bricks and clay – we weren’t short of clay – and worked out how to case harden ordinary mild steel, to give a surface layer of hard steel which we could sharpen. The working parties that went out had strict instructions: any piece of metal you come across, you bring home if you can carry it. The best thing they brought back was pieces of cars; the leaf springs were worth their weight in gold because they were good steel and you could harden it.

The cup I made for the camp bridge club at the Tatura camp.

I built the lathe it was turned on in the camp.

We had all sorts of classes, lectures, and actually got papers from the universities. And a few guys actually did the high school certificate and one of them did his first year B.A. studies, in camp, with help from the university.

I did an engineering course run by a very pleasant German Engineer, who drew us the machinery on a huge blackboard so beautifully, that when I got to see the machines, I walked straight up to them and operated them.

Meanwhile, some people in camp had friends in England who knew someone who knew someone, and there was a White Paper issued in the British Parliament and the whole miserable story was read out in Parliament. That was when we were officially recognised as friendly aliens, but that didn’t mean they opened the gates and let us out. We just became interned friendly aliens.

As time went by, the government realised the mistake they made and they were looking for ways of employing us. We were given the opportunity to join the Australian Army in the labour battalion, and we also had the choice of going back to England, and joining the Pioneer Corps in England. Neither of which appealed to me particularly, because I wanted to join the Army, not a Labour Corps.

They asked me if I would go back to England, but I was very happy to be here, except that I couldn’t do anything to get my parents out.

Slowly people started to be released. A physicist who was in the bunk next to me was gone one morning, and as we later found out he went to America to work on the Atom Bomb. Lecturers, mathematicians were slowly released one by one to the various universities and then finally I got a call up. By that time I had given my occupation as an engineer, as a fitter and turner, and I was called up, one year and ten months after my internment in Australia, to go to a factory in Melbourne. And off I went.